The story of Hip-Hop and Comics is long and convoluted. Hip-Hop began as a communal expression, a bunch of kids in the South Bronx looking for a way to have a good time and move away from the world of gangs and crime that filled their day-to-day lives. Parties in parks and housing projects, new styles of dance and visual art, a new way of playing records, a new method of musical vocalization – over the course of the 70s, these disparate threads wove themselves into one unified youth culture.

But due to the natural way the movement evolved, documentation is spotty. Nobody expected that people would pay attention, contemporary accounts are scarce, and memories are highly subjective. It’s difficult to determine exactly all the details and make it into a linear story. So, I think it’s best to let the picture come together over time, and let the details fill themselves in.

Comic books have been an element in Hip-Hop since the beginning. DJs, MCs, and breakdancers created fantastic identities as if they were themselves costumed crimefighters, graffiti artists borrowed elements from the four-color fantasies they’d grown up reading, flyers for parties and gigs utilized all manner of superheroic iconography. As the movement grew beyond its original boundaries of NYC neighborhoods and rap records became an industry unto themselves, the bonds grew even stronger: groups were pictured in exaggerated poses, superlatives were affixed to artists’ names, outlandish and colorful identities became a trademark of the burgeoning Hip-Hop culture.

But comic books were slow to respond. Marvel, DC, and Archie Comics nodded to Hip-Hop’s popularity, introducing breakdancers and rappers into their titles – but those were simply Hip-Hop comic characters. It was time for a Hip-Hop Comic. And like all Hip-Hop innovations, it wouldn’t happen in the mainstream. It had to come from the underground.

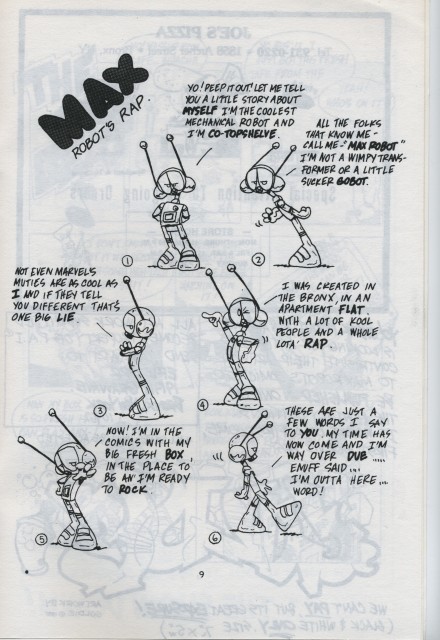

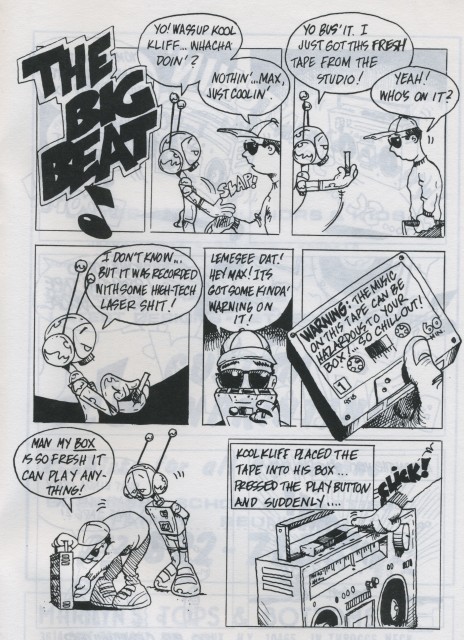

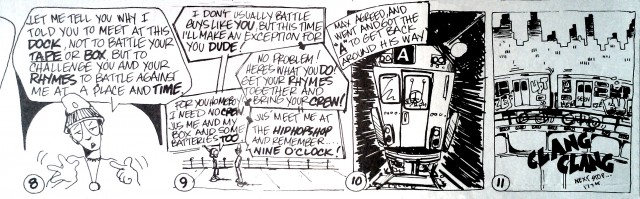

In 1986, NY artist Eric Orr published the first issue of Rappin’ Max Robot. Orr had already made a name for himself as a graphic artist, and he self-distributed this 12 page pamphlet in record stores and comic shops around New York. His cartooning style is loose and energetic, taking cues from underground comics and graffiti art and creating something new and fresh in the process. There are echoes of Vaughn Bodé characters in Max’s design, and a freedom of line and expression in the quick paced pages that speak directly to the spirit of Hip-Hop as it was created: a group of people taking the best parts of the past and remixing them into something fresh and new.

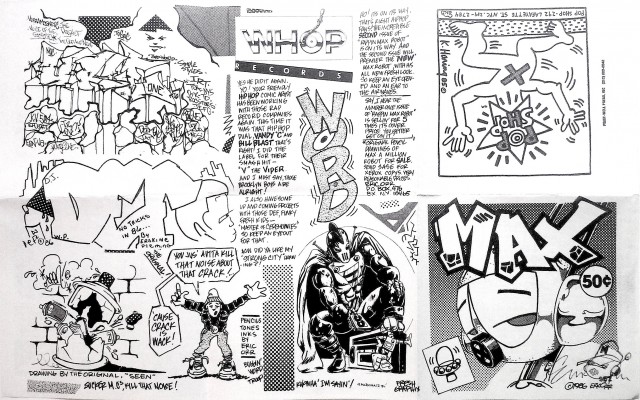

Orr followed up #1 with two special editions, both folded 11×17″ zines that sold for 50¢ each. The full-page stories followed Max as he carried his boom box to and fro, rode the A and 6 trains around town, and schooled an aspiring MC in a rap battle. The flipsides of the issues featured fan art, news items, an announcement of a Rappin’ Max t-shirt, random doodles, and ads for Keith Haring’s Pop Shop boutique in SoHo. (Haring was a friend of Orr’s, a supporter of his work, and the two had collaborated on a series of installations in NYC Subway systems.)

And that was it for the Max comic book. Orr created a “Maxwell Robot” strip that ran in Rap Masters magazine, and went on to great acclaim as a graphic designer for record labels and groups, creating logos for artists and companies including Busy Bee, Masters Of Ceremony, Ultimate Force, Jazzy Jay, Rowdy Records, Strong City Records, Lord Finesse, and the Diggin’ In The Crates (D.I.T.C.) Crew. His most recent comic work appeared in 2010 in the first issue of Wooster Comix, an anthology published by graffiti and street art archivists The Wooster Collective. Orr continues to use a robot as a personal trademark to this day, incorporating variations on the character and image in his paintings and other artwork (including his limited edition Serato control record).

This was it, ground zero, the first Hip-Hop comic – an amazing document of a time, a place, and a developing culture; a printed pipe-dream fueled by beats and rhymes and full of funky robotics.

Rappin Max Robot #1 was printed in an edition of 500 copies, and 250 B&W copies were printed of Special Editions #1 and #2. None of the three have been reprinted. More about the artist can be found at his website and on his facebook page.

All articles in the Hip-Hop Comics series can be found here.

I’d love to show you my hiphop comic I created in 96, just 10 years after. “Hard Rockz n Cotton Candy”. I didn’t know anyone made a comic before me! Then. I met Eric! lol & I used to hang out at Keith’s studio in soho back then too… 🙂 any how’s, the beat goes on… Bless spaze.