Hip-Hop comics are difficult to define, much as Hip-Hop itself is. They’re an entirely different thing than Pop Music Comics, and they deserve their own forum for discussion. This is an important distinction to make, because Hip-Hop is more than just music; it’s a culture based around four elements – the music (DJing), the words (rapping / MCing), the dance (B-Boying), and the visual art (Graffiti). And to trace these elements as they’ve been woven into comic books is to discover the story of a culture as it goes global: a youth movement started in The Bronx in the 1970s becoming part of the fabric of everyday life for millions around the world.

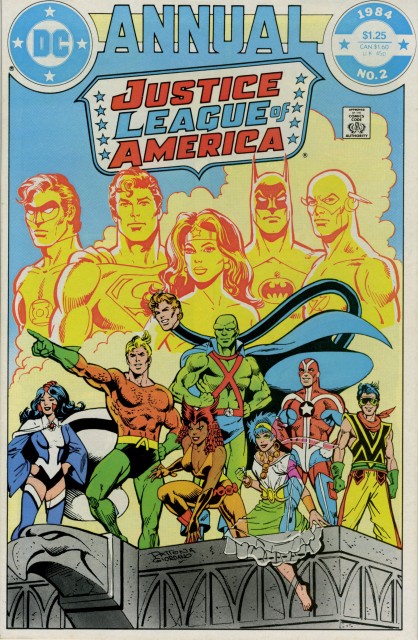

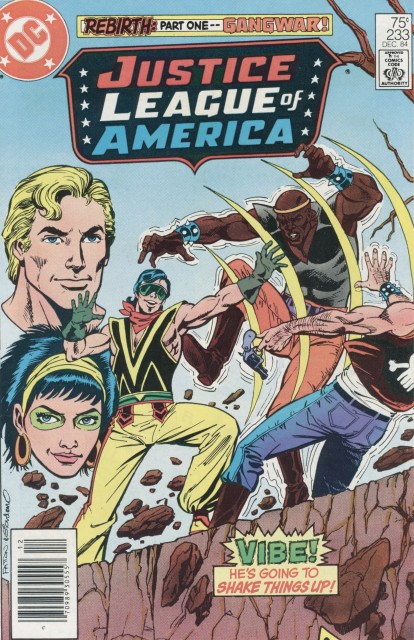

Hip-Hop crept into comics in a number of ways over the course of the 80s. The most obvious elements came first, breakdancing and rap music appearing as background details or as fodder for throwaway gags. But it wasn’t too long before the big two superhero companies capitalized in a big way. The first mainstream character to cash in on the up-and-coming craze was Vibe, a teenage breakdancing Puerto Rican ex-gang member who made his initial appearance (without any backstory or explanation) in 1984’s Justice League of America Annual #2, then got a proper introduction a couple months later, in Justice League of America #233.

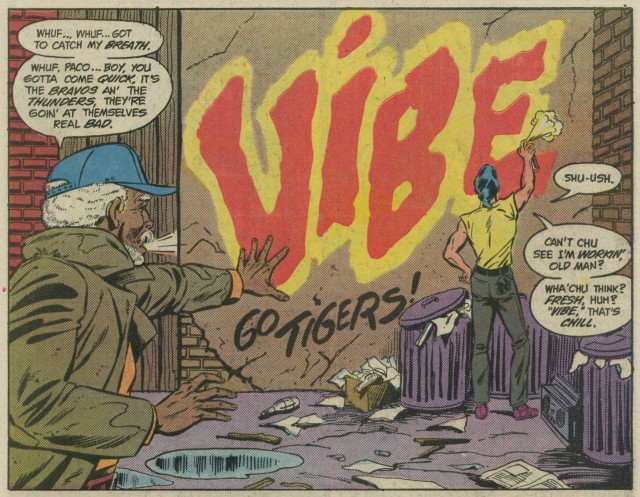

Young Paco Ramone first appeared in the middle of the issue, showing up as a newly restructured Justice League settled in to their new home in Detroit. He made an immediate impression: spray painting ‘VIBE’ on a wall, thwarting a gang uprising, trash talking, and revealing astounding agility and the ability to project powerful shockwaves.

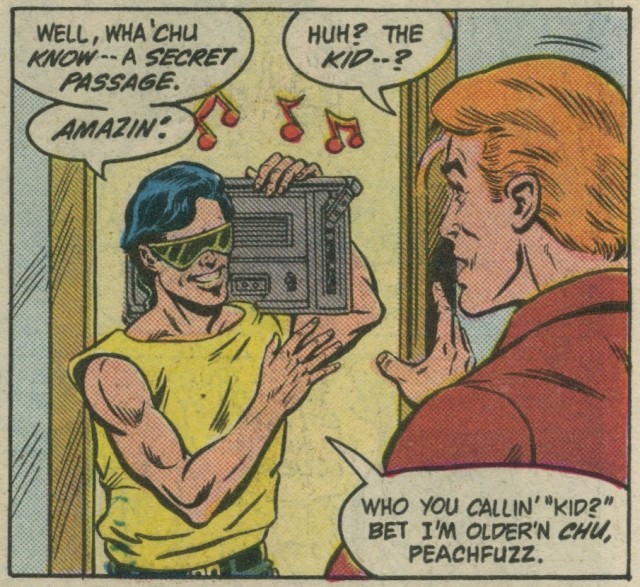

Shortly thereafter, he moonwalked into JLA headquarters, boombox on his shoulder, and became the newest member of the storied superteam. He was young and arrogant, he spoke with an exaggerated accent, and he danced really well. No background checks were conducted, no references were needed; he just put on a costume and jumped straight into battling evil with the big boys.

Sadly, this was not one of those cases where a character is given time to develop beyond their initial one-dimensional portrayal. Vibe stuck around for just over two years, battling crime, adding dramatic tension, doing occasional spins and backflips. He got a new costume, he got in arguments, he got punched out by Green Arrow – and then he got strangled to death by an evil robot in JLA #258, unceremoniously ending DC’s hip-hop outreach initiative.

[Vibe was created by Gerry Conway and Chuck Patton. He has appeared in various flashback stories in the years since his demise, was briefly resurrected as a zombie Black Lantern in DC’s 2009 color-coded crossover epic Blackest Night, and recently starred in his own short cartoon as part of Cartoon Network’s DC Nation programming block.]

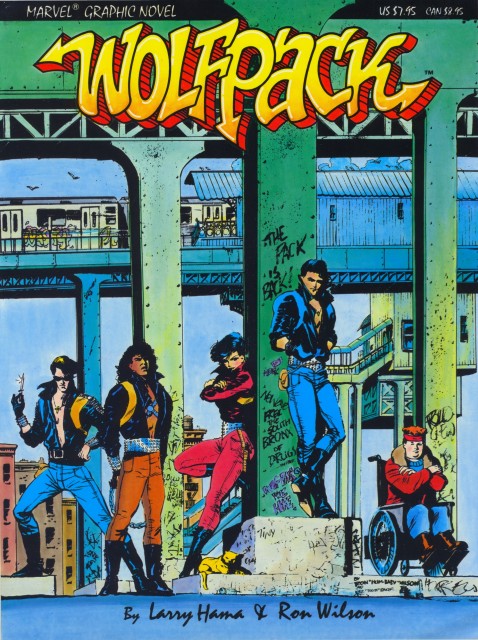

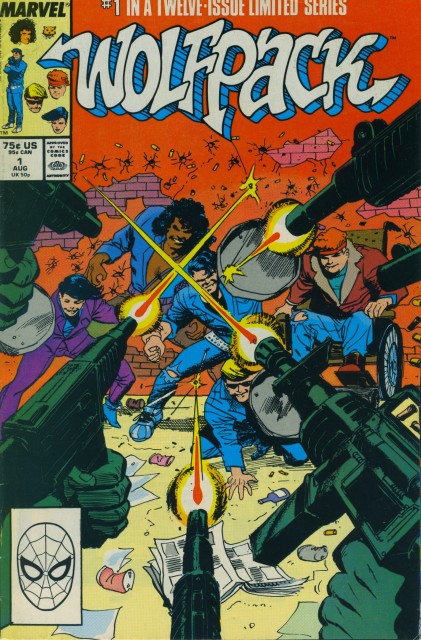

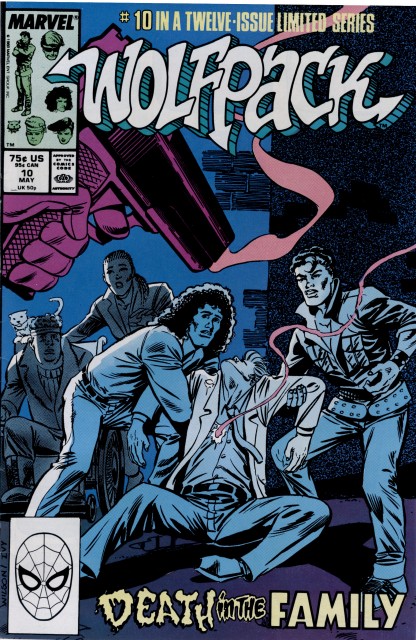

Marvel didn’t jump fully into the urban exploitation sweepstakes until 1988, but once they did, they didn’t hold back: Wolfpack launched with an oversized graphic novel, and was immediately spun off into a twelve-issue limited series. The eponymous ‘Pack was a multi-cultural group of kids (Slippery, Sharon, Rafael, Slag, and Wheels), who were recruited by a mysterious gentleman to learn ancient fighting techniques and battle an evil band of ninjas. The series was set in the South Bronx, the birthplace of Hip-Hop, and featured numerous references (both subtle and not) to the culture. Even the front cover logo was clearly based on graffiti lettering styles.

G.I. Joe scribe Larry Hama and longtime Power Man artist Ron Wilson created and launched the series, and they seemed to be shooting for a story that combined elements of Fort Apache: The Bronx, The Breakfast Club, and Frank Miller’s Elektra saga. Classroom problems, burned-out vacant lots, and grand conspiracies were delicately balanced; the focus stayed on the kids at the heart of it all, dealing with an out-of-control world as best they could.

But almost immediately, the book was troubled with shake-ups. Co-editor Ann Nocenti moved on after the first issue. Inker Kyle Baker was replaced by Chris Ivy after the first four issues, drastically altering the look and feel of the story. And Larry Hama left after issue #3, taking with him any plans for the series’ overall arc.

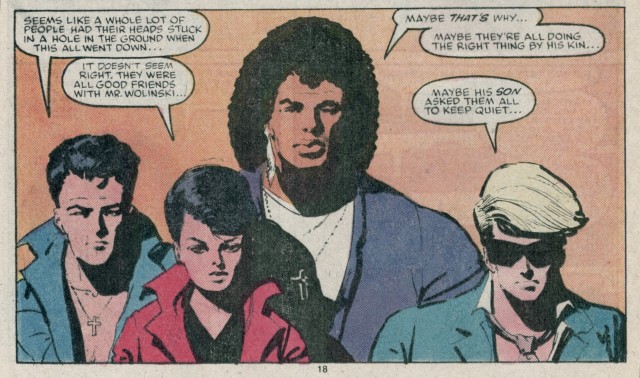

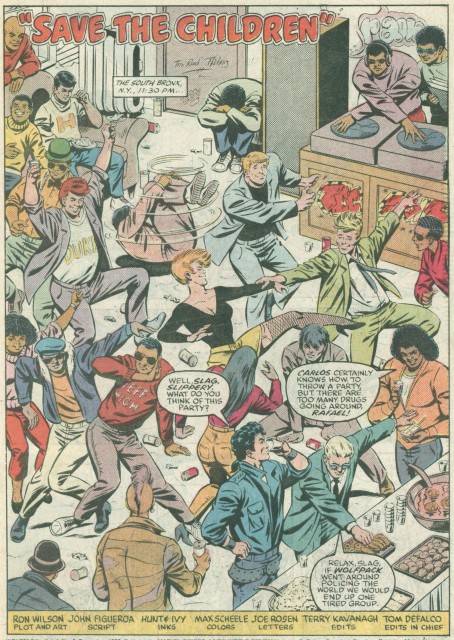

Penciller Wilson did plotting/art double duty for issues 4-6, and the change in direction was immediately noticeable; the plot swerved away from mystical heroics and began to focus more on realities of the Reaganomics-riddled inner city. Crack dealers were preying on the weak, and a clueless police force was powerless to effect change. Ninjas weren’t the greatest threat anymore: drug use, domestic abuse, and widespread corruption were the order of the day. It was clear (despite the sanitised Marvel Comicness of it all) that someone with an actual passing knowledge of urban culture had taken over, and Hip-Hop culture began to be utilized in a more direct fashion: issue #5 opened with a scene of a party in a rec room, complete with a DJ and kids dancing to RUN-DMC records.

But this, too, was short-lived. John Figueroa became the title’s sole author for the final six issues, and what little sense and consistency the book had reacquired quickly evaporated. The Boogie-Down Bronx was transformed into a world of ham-fisted stereotypes and senseless hyper-violence. One member of the Wolfpack (Sharon) gets shot in the spine by a drug-addled trenchcoated hitman, is paralyzed, and nearly dies. One of the other kids (Slippery) is gunned down while attempting to rescue a young child from gang members.

Things proceeded to fall apart in a blur of Rambo headbands, crowbars, leather vests, samurai assault squads, preachy plot devices, and nihilistic bloodshed. The evil junkie assassin that shot and nearly killed Sharon returns, reformed and rehabbed, and somehow convinces everyone that he’s a nice guy now. He takes over training and leading the group, and instructs the kids in proper usage of assault weapons.

In the final issue, they bumrush the Manhattan headquarters of the nasty secret society, entering with guns blazing, mowing down anyone who stands in their way. It’s a jarring shift in intent and mood, the kung-fu kids who’ve lost family and friends to gun violence suddenly adopting automatics and advocating murder. If I had to guess, I’d say it was an attempt to capitalize on the sudden success Marvel was having with The Punisher in the late 80s; an editorial edict on the order of “what sells is morally ambiguous characters with lots of firepower, so fit that into this struggling mini-series that we’ve already committed to releasing”. Still, it’s ASTOUNDING how badly it fits in here. It’s out-of-place, inconsistent with all that’s gone before, and seriously disturbing.

But hey, the good guys win. The evil corporation/ninja cabal/centuries-old warrior clan/crime syndicate is defeated. Apparently the moral of the story is that guns will save the ghetto from itself.

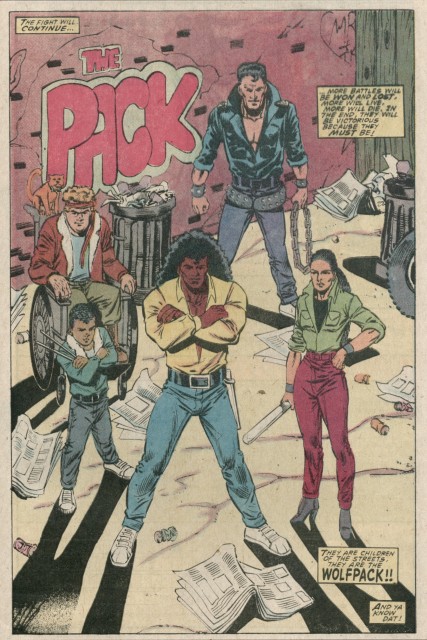

And as one final nod to the urban culture that’s being exploited, there’s an epilogue: a full-page shot of the still-surviving ‘Pack members standing in an alley, throwing up their best stances, the wall behind them dripping with self-promoting graffiti. In case you missed just how ineptly pandering/patronizing it is, the caption drives the point home: “They are the children of the streets, they are the WOLFPACK… And ya know dat!” There’s so much wrong with this, from the sudden adoption of phonetic spelling in the narration, to the appropriation of a classic rap phrase in one last bid for cool points.

So, despite some flickers of potential, the series flames out in spectacular fashion. There were some good moments, but the overall picture is something between mediocre and just plain offensive. Some of the creative team were clearly invested in the project, but the constant changes in personnel and creative intent were too much for anyone to overcome. Marvel would go on to showcase Hip-Hop culture to great effect in a variety of titles, but these first steps were tentative and ill-considered.

[The Wolfpack have remained in mothballs since the end of their eponymous miniseries, though a parallel take on the team briefly appeared in the 2008 alternate-reality title House Of M: Avengers.]

All articles in the Hip-Hop Comics series can be found here.