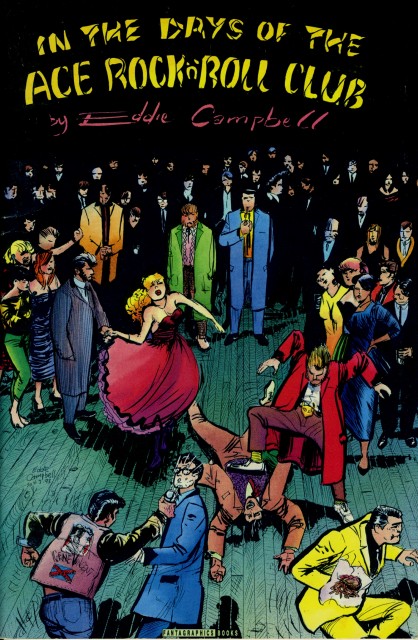

In the late 70s, Eddie Campbell wrote and drew a handful of short stories tracing the ins and outs of a group of Teddy Boys in Southend. He called them “In The Days Of The Ace Rock ‘n’ Roll Club”, and while they’re not specifically about pop music, music plays an integral part in them. It’s right there in the title; the music provides the setting, lays the groundwork, and sets the tone for everything that happens.

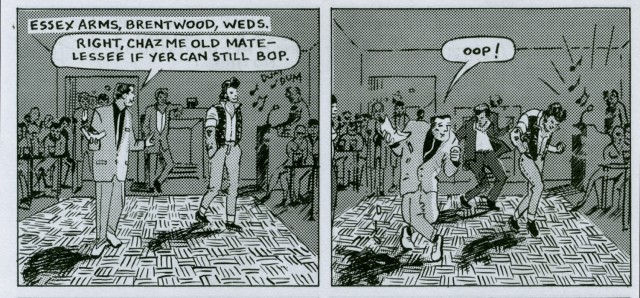

The pieces are part auto-biographical, part anecdotal, part fiction, but they’re clearly set in a real time, in a real world. And the characters function as real people: they’re young, they work hard at looking good, they drink, they go out, they fight, they tangle and disentangle with others of their kind. They exalt their own existence as they move through it, living life, searching for moments of meaninglessness in the midst of the deeply important world. There’s fun to be had, people to make out with, songs to be danced to.

The text creates entire worlds with accents and dialogue, and the visual atmosphere is evoked with thin pen lines, grey washes, and some Zip-A-Tone textual effects: expanses of cafes and cigarette smoke and slicked-back rockabilly haircuts. And the stories aren’t really stories, but scenes, vignettes of life. Conversations, socializing, laughing, getting in trouble, having sex, singing along to songs, moving along to the next thing.

Reading it now, it seems a clear precedent for Phonogram (which I discussed in a previous article), tracing strands of British youth culture that have stayed constant over generations. One takes place in the post-Quadrophenia era of nouveau mods and rockers, and one occurs in the modern day, when social stratas aren’t nearly as well-defined… But you can draw a clear line across four decades from the Ace Rock ‘N’ Roll Club to The Singles Club.

Granted, there are substantial differences. Ace Rock ‘n’ Roll Club functions as true-life historical fiction, Phonogram is a cumulative portrait of a time and place, with huge brushstrokes of the fantastic. Campbell’s portrait of lives is more literal, Gillen and McKelvie’s is filled with idealizations and overt nods to the mystical powers of music. The two works vary in approach, take different shortcuts, and highlight different aspects of the stories they tell. But they’re equally true portraits of a lifestyle, of a scene, of moments in time that last and linger.

The trappings aren’t what matters. The details vary, but emotions stay constant. Dancing, socializing, and personal relations don’t change, and that’s why these comics (and the songs they evoke) work so well: the important elements are true to life. The devotion to the music, the friendships, and the emotions are truthful, and therefore, so is the story.

The Ace Rock ‘n’ Roll stories were written and drawn in 1978 and 1979, and originally self-published in various black and white pamphlets between 1982 and 1985. A selection were reprinted by Harrier Comics as “Ace” in 1988, and a more complete collection was published by Fantagraphics Books in 1993 as “In The Days Of The Ace Rock ‘n’ Roll Club”. There is no current print edition, but the complete series is available (with plenty of supplemental material) as an iPad app, under the title “Dapper John: In The Days Of The Ace Rock ‘n’ Roll Club“.

All articles in the Pop Music Comics series can be found here.