In the 1950s, Walt Disney’s empire grew hugely, expanding into records, live action films, nature documentaries, children’s magazines, theme parks, and (possibly most importantly) the emerging medium of television. The Disneyland TV show launched in 1954, and played a huge part in changing the public image of the company from a mere producer of cartoons to an all-around entertainment powerhouse. Walt himself introduced and hosted every episode; the contents included cartoon selections from the Disney archive, behind-the-scenes looks at the studio production process, newly filmed programming (including the famed Davy Crockett series), and documentary, historical, and scientific pieces.

Three episodes broadcast between 1955 and 1957 (Man In Space, Man On The Moon, and Mars And Beyond) dealt with man’s fascination with space, and utilized some of the world’s foremost authorities on aeronautics and rocketry to help envision the future of space travel. And since Dell Comics had been having great success with their line of Disney tie-ins, the shows were then adapted into print form.

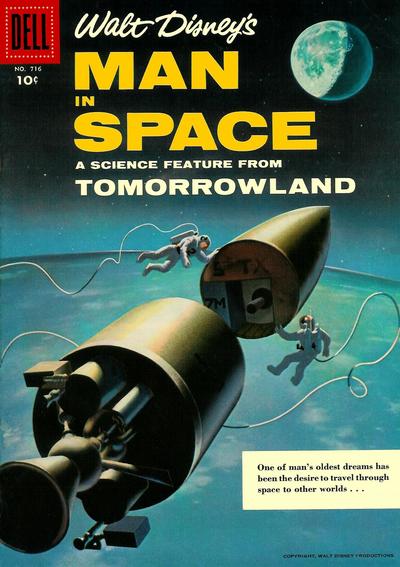

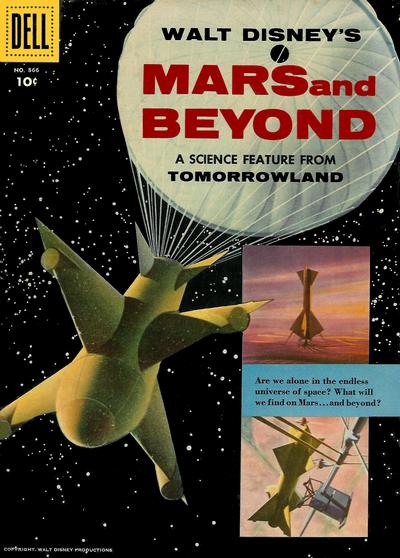

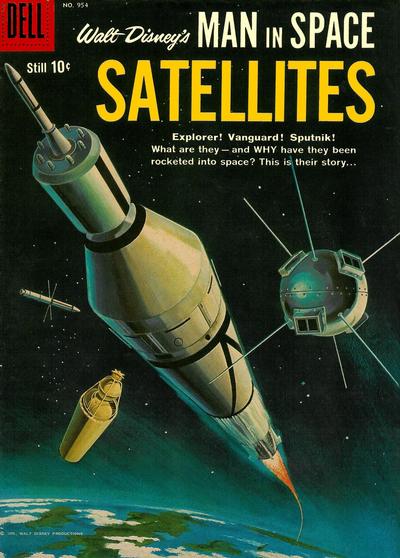

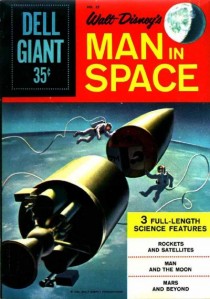

The first comic, published as Dell Four Color #716, was entitled simply Walt Disney’s Man In Space and reworked material from the first two TV programs. The second, Dell Four Color #866, was called Walt Disney’s Mars And Beyond, and translated that episode into text and art. And a third issue, titled Walt Disney’s Man In Space: Satellites, was published in Dell Four Color #954 and contained all original material. The issues were successful enough that they were eventually collected in 1959’s Dell Giant #27, reprinted under a cardstock cover for the then-imposing price of 35¢.

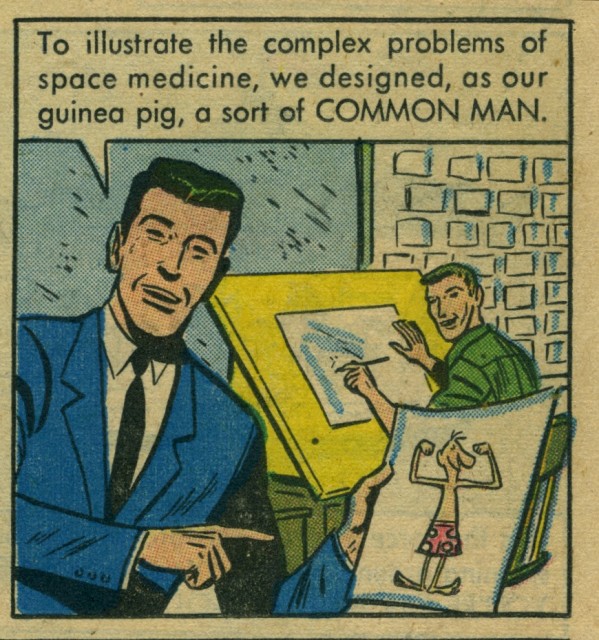

Regardless of format, they’re amusing and enjoyable comics, full of gee-whiz excitement over the possibilities of space exploration. All three were scripted by veteran comic and cartoon writer Don R. Christensen, and they move quickly through facts and figures, recountings of aviation history, and predictions of the forms space travel will eventually take. (After all, there was still more than a decade to go before a man would set foot on the moon.) The art was provided by Tony Sgroi, a former animator at Warner Brothers and Walter Lantz Productions, and his drawings move from formal realism to fluid caricature as each scene demands.

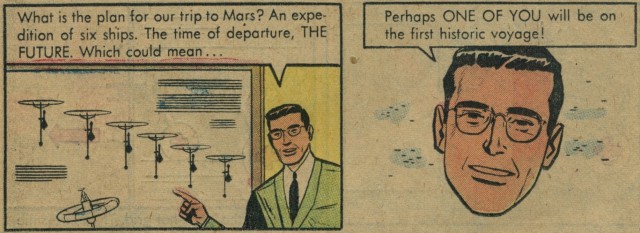

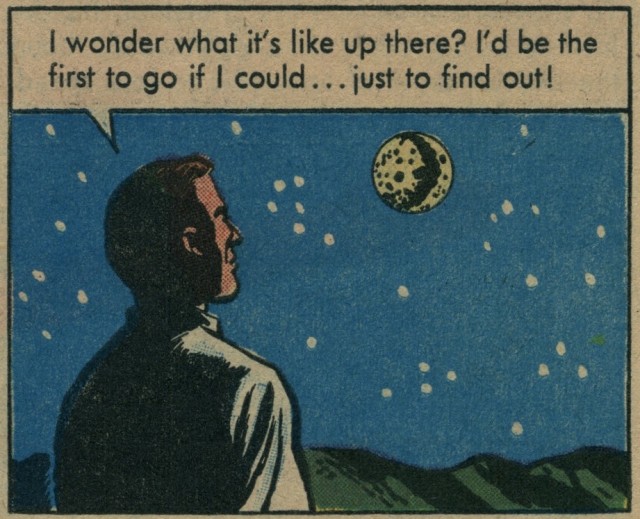

The first comic, Man In Space, is a pretty straight-ahead lesson on space travel as it was known at the time. There’s some speculation, some fun historical anecdotes, and a lot of technical looks at what it would take to get humans past the boundaries of earth’s atmosphere. It’s fairly standard stuff, save an oddly touching one-page interlude of existential quandary, as the narrator ponders the enormity of space and humanity’s place in it. It’s pretty heavy for a kid’s comic, even in the height of the post-war atomic era.

The typeset text (rather than the usual comic book hand-lettering) makes it all seem a bit stiff and academic, but the pervading sense of wonder ensures that it manages to both educate and inspire.

Mars And Beyond, the second of the comics, is entirely devoted to man’s eventual journey to the red planet, and the difficulties and benefits of undertaking such an expedition.

This certainly contains the shakiest science of any of these three issues, but it’s largely due to the lack of facts available. There’s pages depicting possible Martian life forms and the imagined terrain of the planet. The plan outlined for a fleet to reach the red planet and set up base is inspired, but is largely conjecture. But it doesn’t matter. Each generation is limited by its technology; at the time, this was as good as it got.

And then there’s the third of the comics, Satellites. There are more diagrams and lecturing here, less of the whimsical asides that lightened the mood of the other two issues… Yet there’s still a palpable sense of optimism underlying the proceedings: the dreams of a future where space travel leads to an end of famine and war, and eventually a united humanity. I get wistful looking back at a time when science was so clearly the way forward, absurd as it may seem today.

It’s also worth reiterating that while these issues seem odd and quaint in retrospect, they were as accurate as they could be, given the technology on hand. In fact, the first two won their creators Thomas Edison Science Foundation awards in 1956 and 19571. They achieved their goals of teaching in an entertaining fashion, and getting kids interested in exploring the universe.

It’s a bit sobering to think that there’s nothing like the space race today, no grand plan for mankind to reach beyond their grasp, to embark on the next great frontier of human achievement. But that’s what I enjoy most about reading these books, the perspective on what the future used to look like. The hope and foresight is ridiculous by modern standards. It’s pure space-age positivity. And it’s glorious.

The three episodes of Disneyland that inspired these comics were released on DVD in 2004, and are available on Amazon. The comics themselves have not been reprinted since 1959, but can be found through eBay or comic shops dealing in vintage back issues.

1Walt’s People Vol. 11, edited by Didier Ghez, Xlibris 2011.