By the way, this is not going to be a scholarly, informative lecture series about the long-running TV series. I might point out a tidbit or two you hadn’t heard, but I’m no expert or insider. There are countless resources that can tell you everything you didn’t really need to know about M*A*S*H. I’m not going to bother. I can barely sit through the “special features” on the DVD set without climbing out of my brain with boredom. I don’t really care that much about the minutia, I just want to talk about the show.

So. The pilot episode.

In the first 2:49 we see a spectacularly concise expository snapshot of the show’s main characters, setting, and tone. Granted, they were building off of a successful series of books and a feature film, so the characters were already pretty well-defined, a luxury I’m not sure many pilot episodes are afforded. But watching it now, in retrospect, it’s astounding how much they got right from the opening frame.

We see Hawkeye and Trapper John wearing Hawaiian shirts, chipping golf balls into a mine field located yards away from the camp. Trapper sets off a mine with his shot and they cheer. Zany, irrevrent guys staring death in the face and making a good time of it. Check.

We see Hawkeye and Trapper John wearing Hawaiian shirts, chipping golf balls into a mine field located yards away from the camp. Trapper sets off a mine with his shot and they cheer. Zany, irrevrent guys staring death in the face and making a good time of it. Check.

We see Henry Blake and a pretty nurse, in scrubs, looking serious as they huddle over, perhaps, a complicated surgical procedure. Pop! goes the champagne cork and they kiss. Drunken workplace sexual misconduct. Check.

We see Frank and Margaret sitting across from each other and studying the Bible. Pan down, they are barefooted and their toes are entwined. Moralism masking a clandestine affair. Check.

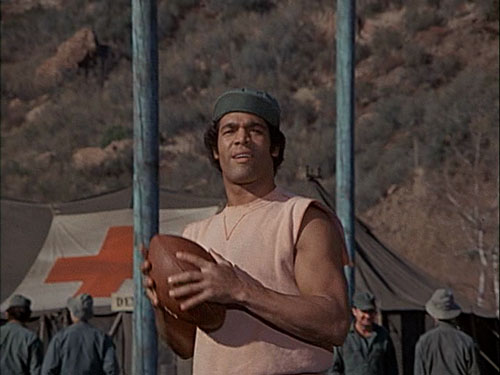

We see Spearchucker and Radar tossing a football around. Radar pauses, looks to the sky, says “here they come!’ A voice: “I don’t hear anything…” and Radar says “wait for it,” as the choppers appear in the distance, just cresting the hills. It’s a scene we will see, in some permutation, hundreds of times before the series ends, 11 years and 250 episodes later.

We see Spearchucker and Radar tossing a football around. Radar pauses, looks to the sky, says “here they come!’ A voice: “I don’t hear anything…” and Radar says “wait for it,” as the choppers appear in the distance, just cresting the hills. It’s a scene we will see, in some permutation, hundreds of times before the series ends, 11 years and 250 episodes later.

The series theme song “Suicide is Painless” begins to play, and the voiceover of the PA, for the first of countless times announces: “Attentional all personnel. Incoming wounded.” Interspersed among the credits are emblematic shots of medical personnel rushing toward the choppers and doctors leaning over the camera-as-wounded-soldier, shouting out orders.

Thorough exposition in less than three minutes.

Thorough exposition in less than three minutes.

This pilot is riddled with sexual innuendo which was a legacy from the rated R film and sexism that is surely accurate to the 1950s. While the “charming and insistent doctors chasing insincerely protesting nurses” device remains until the bitter end, it becomes less and less a go-to gag and more just one thing — the bad food, the uncomfortable beds, the dirty clothes — that illustrates the daily life of a M*A*S*H unit during the Korean War. This episode seems to fall to those sexist gags with a degree of embarrassment, almost like “well, the audience is expecting us to go there, and we can’t let them down.” For example, when Hawkeye refers to Margaret as “Baby,” in what should be an offhand way, it is jarring and feels false.

Alan Alda is a well-known feminist, even spearheading the ERA Countdown campaign with then-first lady Betty Ford in the mid 70s. So. You know. Maybe that has something to do with it. And it’s common gossip that he was uncomfortable with the lighthearted attitude towards war and made some demands of the show to make sure the the seriousness of war was not lost: there was at least one surgery sequence in every episode, and though the show’s rather liberal use of a laughtrack, there was never any laughter in the OR scenes.

Alan Alda is a well-known feminist, even spearheading the ERA Countdown campaign with then-first lady Betty Ford in the mid 70s. So. You know. Maybe that has something to do with it. And it’s common gossip that he was uncomfortable with the lighthearted attitude towards war and made some demands of the show to make sure the the seriousness of war was not lost: there was at least one surgery sequence in every episode, and though the show’s rather liberal use of a laughtrack, there was never any laughter in the OR scenes.

Over the 11 year run of the show, many things, of course, change. From concrete things like characters coming and going and to more esoteric changes like the show’s gradual evolution from episodic comedy to serial drama.

The changes from the Pilot to the rest of the series are mostly minor — the recasting of the Fr. Mulcahy character between the time the pilot was shot to the time the next episode aired (and his eventual name change from John Patrick to Frances John). Hawkeye’s referring to his “parents” when eventually his father is repeatedly referred to as a widower. And though, as I mentioned before, even in the pilot episode, the OR had no laughtrack in order to avoid diminishing the seriousness of war casualties, in this episode there is a distinct absence of blood. The surgeons’ gloves are wet as they reach for their instruments, but there is no blood.

The changes from the Pilot to the rest of the series are mostly minor — the recasting of the Fr. Mulcahy character between the time the pilot was shot to the time the next episode aired (and his eventual name change from John Patrick to Frances John). Hawkeye’s referring to his “parents” when eventually his father is repeatedly referred to as a widower. And though, as I mentioned before, even in the pilot episode, the OR had no laughtrack in order to avoid diminishing the seriousness of war casualties, in this episode there is a distinct absence of blood. The surgeons’ gloves are wet as they reach for their instruments, but there is no blood.

And the ostensible storyline of the pilot is that the camp is raising money to send Ho-Jon, the Korean “Swampboy” who takes care of things for the doctors who live in the tent known as the “Swamp” to college in the states. They hold a raffle for a weekend pass to Tokyo in the company of the lovely Lt. Dish. The raffle is rigged and Fr. Mulcahy wins, saving the engaged Lt. Dish from trouble in Tokyo. And though in the episode, they succeed in raising his tuition, Ho-Jon goes on to appear in several later episodes.

Then there’s the case of Spearchucker Jones, a black surgeon who was phased out in the first season, because, the rumor mill states, the creators of the show discovered that there were no black surgeons in the Korean War. This tale is actually not true. A black surgeon called by the racist epithet “Spearchucker” appears in the Richard Hooker autobiographical novel that went on to spawn the film and then the series. Research shows that there was indeed a black neurosurgeon in the MASH unit he served with during the Korean war. In fact, the loss of the Spearchucker character was likely due to the same evolution that led Wayne Rogers (Trapper John McIntyre) to leave after the 3rd season: the show became more a show about Hawkeye Pierce and less “A Novel About Three Army Doctors,” which was the title of the Richard Hooker novel.

Then there’s the case of Spearchucker Jones, a black surgeon who was phased out in the first season, because, the rumor mill states, the creators of the show discovered that there were no black surgeons in the Korean War. This tale is actually not true. A black surgeon called by the racist epithet “Spearchucker” appears in the Richard Hooker autobiographical novel that went on to spawn the film and then the series. Research shows that there was indeed a black neurosurgeon in the MASH unit he served with during the Korean war. In fact, the loss of the Spearchucker character was likely due to the same evolution that led Wayne Rogers (Trapper John McIntyre) to leave after the 3rd season: the show became more a show about Hawkeye Pierce and less “A Novel About Three Army Doctors,” which was the title of the Richard Hooker novel.

Another thing which notably evolves from this episode forth is the Frank Burns character. The pilot frequently refers to his Bible study and devout faith. Later this gives way to devotion to military order and regulations. I’m thinking that they chose to shy away from a staunchly religious man’s extramarital affair, in order to make the relationship with Margaret less hypocritical and more ridiculous. The implications of religious fervor are apparently not as funny as watching a pair of fervent military tightasses constantly undermined by a bunch of buffoons, and so in later episodes, Frank’s religiosity is only one aspect of his conservative nature.

But what I am more struck by as I watch the pilot, after all these years, is not the things which changed but the things which remained the same. The character of Radar O’Reilly and his relationship with Lt. Col. Henry Blake: they nail it from the start. That device was repeated over and over and over again, and Henry’s startled irritation and Radar’s disaffected insistence never waver. It’s perfect from the very first instance. And it never gets old.

But what I am more struck by as I watch the pilot, after all these years, is not the things which changed but the things which remained the same. The character of Radar O’Reilly and his relationship with Lt. Col. Henry Blake: they nail it from the start. That device was repeated over and over and over again, and Henry’s startled irritation and Radar’s disaffected insistence never waver. It’s perfect from the very first instance. And it never gets old.

Another often repeated plot point is the one in which Hawkeye and his cohorts engage in some forbidden activity, get caught, and are threatened with court martial. Without fail, this threat is followed up with a moralist speech about The Really  Important Things In Life and a reminder that these doctors are necessary for the saving of lives and subsequently, their hijinks are overlooked, much to the chagrin of Burns and Houlihan. In this episode, when the General du Jour (the 4077th’s superior officer changes often throughout the run of the show, but he’s always more or less the same character) storms in and calls for the MPs Hawkeye makes The Speech, the one that goes something like, “You’re about to hear choppers filled with kids who went to a different party tonight. And without us, a lot of those kids won’t make it home form the party.” Cut to OR sequence, followed by the General du Jour’s proclamation that these are the best meatball surgeons he’s ever seen.

Important Things In Life and a reminder that these doctors are necessary for the saving of lives and subsequently, their hijinks are overlooked, much to the chagrin of Burns and Houlihan. In this episode, when the General du Jour (the 4077th’s superior officer changes often throughout the run of the show, but he’s always more or less the same character) storms in and calls for the MPs Hawkeye makes The Speech, the one that goes something like, “You’re about to hear choppers filled with kids who went to a different party tonight. And without us, a lot of those kids won’t make it home form the party.” Cut to OR sequence, followed by the General du Jour’s proclamation that these are the best meatball surgeons he’s ever seen.

A whole laundry list of bits are to be repeated over and over throughout the subsequent 250 episodes: Hawkeye’s “Dear Dad” voiceover, the affair between Hot Lips and Frank stymied in some hilarious fashion, Henry refusing to give Hawkeye A Thing That He Wants and Radar tricking him into signing for The Thing Hawkeye Wants anyway, the flashbacks to Hot Lips and her affairs with generals, martinis and the still, and Hawkeye’s ubiquitous red bathrobe.

But bits and devices and repeating plot twists aside, the characterization and the actors’ portrayal of these roles are striking, from this pilot episode forward. The pacing, the writing, and the performances are already firmly in place. You could drop this episode in anywhere during the first few seasons and it would fit seamlessly.

But bits and devices and repeating plot twists aside, the characterization and the actors’ portrayal of these roles are striking, from this pilot episode forward. The pacing, the writing, and the performances are already firmly in place. You could drop this episode in anywhere during the first few seasons and it would fit seamlessly.

In short, it’s clear that they got so much of it it right, from the very beginning.

1 comment for “M*A*S*H Revisited: The Pilot Episode”